(sJacas)

A friend of mine, a childhood Chicago Bulls fan, once told me he refuses to watch replay of the historical Game 6 of the 1998 NBA Finals. He doesn’t want his childhood memories ruined. Having watched said game myself years after it took place, I am certain he is doing the right thing. Subtract the magnitude, the end-of-an-era charm and you’re left with a stagnant, 48-minutes iso-feast, during which Michael Jordan took more than half of his team’s shots. He missed 20.

I always expect to come away disappointed from watching tape of an all-time classic. Most people will tell you the 2002 Final between Kinder Bologna and Panathinaikos was one of the best in modern Euroleague history. It had Bodiroga, Obradović, Ginobili, Rigaudeau, Smodiš, Messina, a large first half lead, a comeback, worthy star performances, a fired-up crowd and tension until the last minute. And yet — guess what — players missed shots. They committed dumb turnovers, left the backdoor open, failed to box out, missed fouls shots, just as they do today. 65 free throws too often brought the game to a standstill. All things considered, it was a great game.

No-Position Basketball

With the 2002 Final, it is not even the inimitable style of play of prime Bodiroga and about-to-reach-superstardom Ginobili that strikes me.

It is the modernity of the two teams.

Dušan Ivković, in 2012, said that it is his “unfulfilled wish to coach a team consisting of five players who are 2 meters tall, run the floor, pressure the ball and take advantage of mismatches”. George Karl, in 2014, thinks that the game is going to “no-position” basketball players.

Twelve years earlier on May the 5th 2002, Željko Obradović had fielded a starting lineup of — official numbers — 195 (Mulaomerović), 198 (Kutluay), 206 (Alvertis), 205 (Bodiroga) and 204 (Middleton) centimeters for the Euroleague Final. A matchup nightmare and, with the exception of Middleton, “no-position” basketball. Four basketball players were advancing the ball upcourt, running pick and roll, posting up or coming off the pindown screen. Ettore Messina himself had a freakishly tall roster at his disposal, starting Marko Jarić (201 centimeters), Manu Ginobili (198) and Antoine Rigaudeau (199) at the one, two and three. Jarić for most of the game had the task of limiting Bodiroga, who was playing forward only on paper, there was no position. Bodiroga delivered a MVP-worthy performance, scoring over the smaller defender one possession before sucking in the defense and delivering deadly kick-outs the next trip down the floor.

The 2002 Panathinaikos team was not dissimilar in its setup to later Panathinaikos versions and even 2013-14 Fenerbahçe (there is some versatility in a Bogdanović, Preldžić, Bjelica two, three, four). But none possessed a forward quite like Dejan Bodiroga. Bodiroga flat-out killed opponents when he was rebounding and pushing the ball up the court. Defense is unorganised in those situations, and Bodiroga always possessed skillset and ball IQ to suck in the defense and create close out situations early on the clock.

Floor-Stretching, Drive and Kickout

Granted, this is 2002. We’re not talking basketball stone age here.

I am not sure why European basketball took this path, but there is little doubt in my mind that basic shot value, not exactly rocket science to begin with, had long been understood by year 2002. Teams were using the high-value spot up three as both floor-spacing- and secondary finishing tool. The main objective was getting layups. Three point shooting ability helped opening up the floor and provided a high-value alternative for layups. Defenses were collapsing early — the paradox in aggressive help defense and three point shot value has been pointed out before — and most likely playing their role in shaping the distinct European drive and kickout style that has been dominating this modern era of basketball.

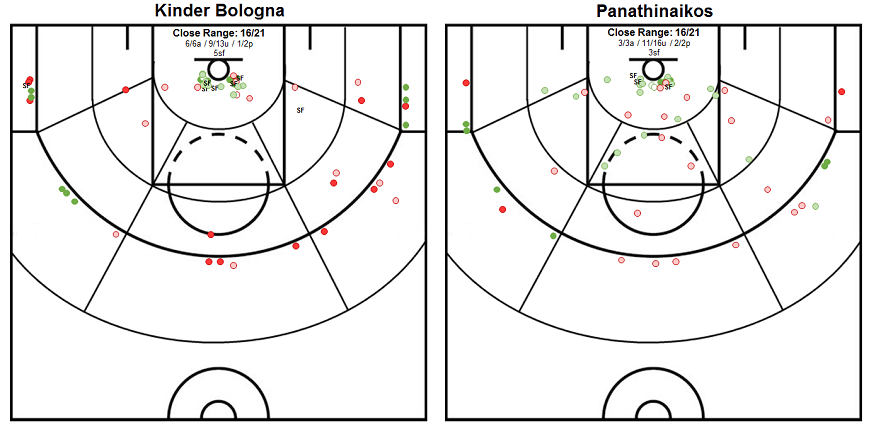

Transparent circles stand for unassisted-, filled circles for assisted shots. Empty circles for putbacks. Heartfelt apologies for not having used the old FIBA court.

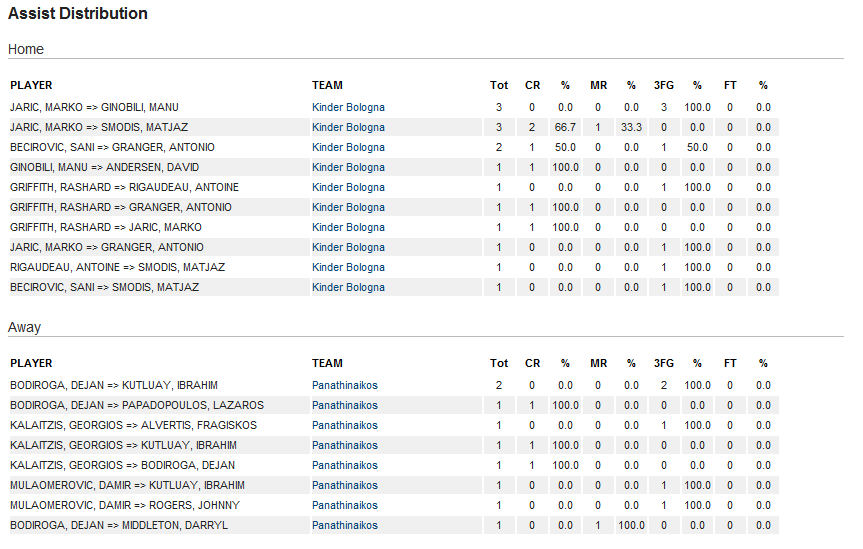

Jarić was particularly aware of this, driving against a collapsing Panathinaikos defense and kicking for plenty of open looks from the outside. Three of such plays are shown below. He had four assists on made three point shots.

This is the play Bodiroga and İbrahim Kutluay iced the game with. A familiar roll and replace, with Johnny Rogers popping up at the three point line. Sani Bečirović is helping one pass away. There was a lot of helping one pass away, and often players were able to recover in time and run shooters off the three point line. Not Kutluay. The man had been in close out situations a billion times. And so he fakes Sani off his feet, pauses for a split second and calmly sinks the three point shot.

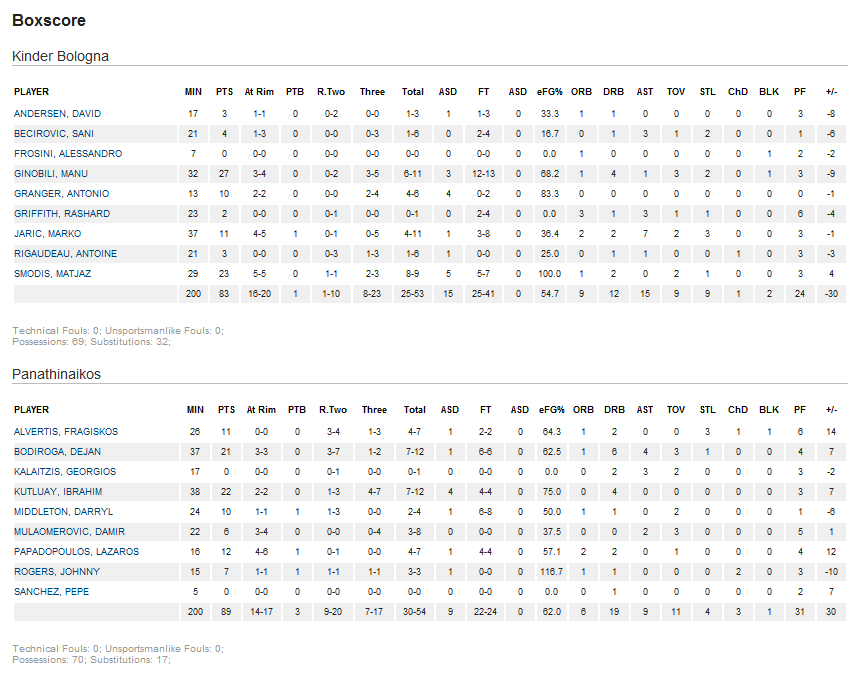

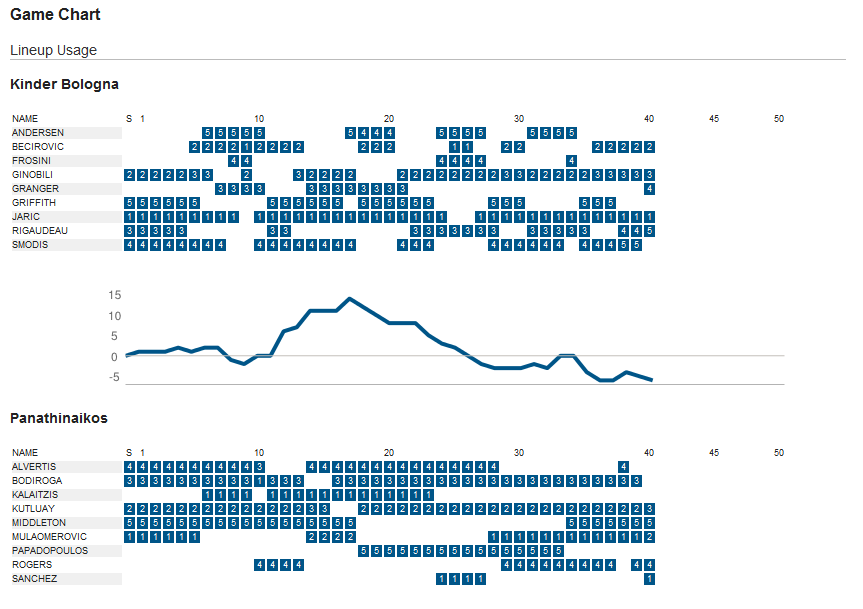

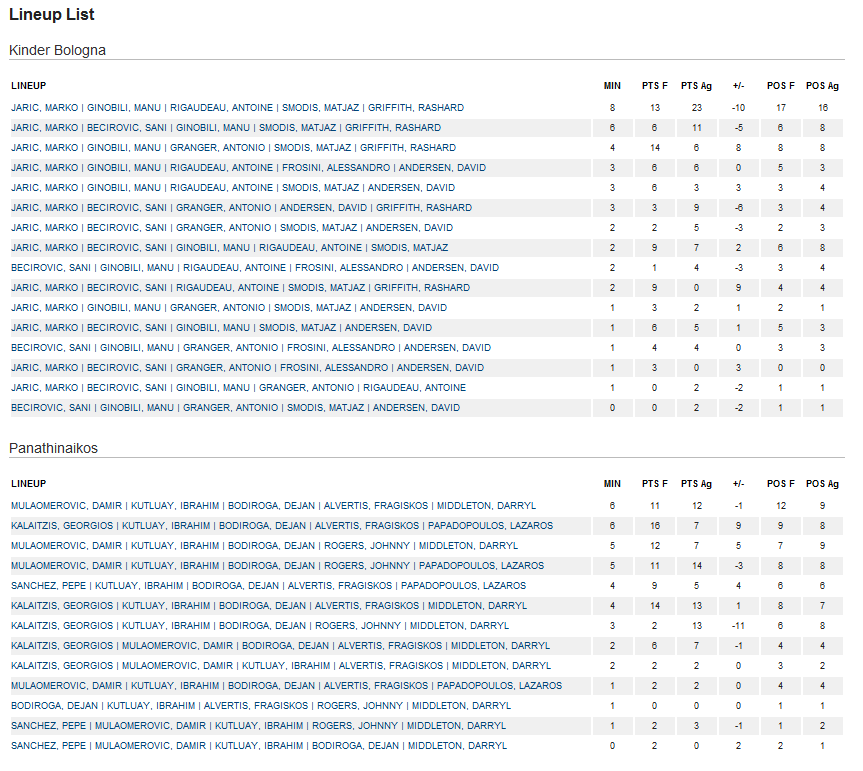

If you’re looking for dissimilarities to the modern basketball game, Obradović’s center rotation looked like this (see attachments): Middleton played from minute one to 17, Papadopoulos (who was fantastic) from 18 to 33, Middleton from 34 to 40. Today a big usually has two to three oncourt sequences.

Loose Notes

- There’s not been a team in modern Euroleague history as young and talented as Kinder Bologna were. They played at a minute-weighted age of 24.3 years, which would qualify for sixth youngest out of 154 teams from ten European top leagues this season.

- When he wasn’t doing primary ballhandling, Bodiroga was often used as a top of the key passing station. Bodiroga was able to see and pass over Jarić and occasionally found the big with the high-low feed.

- Look (see game chart in attachments) how different the substitution patterns were. Obradović was letting his guys play for long stretches, subbing just 17 times, while Messina — foul trouble played a role for Rigaudeau and Griffith — subbbed 32 times. This was a time when playing guys 30-plus minutes was still a regular occurrence. Today it is not.

- 38-year-old Johnny Rogers was Panathinaikos’ unsung (although, wait, I’m sure he was addressed in songs that evening) hero. Rogers took two charges, had a putback, a couple of hard fouls and hit two big fourth quarter shots — a turnaround in the post over Sani and a spot up three from a typical Obradović misdirection play, where Rogers screens baseline for Alvertis and the Mulaomerović pick and roll with Middleton flows into a down screen for Rogers. Wide open spot up three:

- We were addressing guard rebounding (specifically Sergio Rodriguez’ and Vangelis Mantzaris’ commitment to box out big men) in our latest podcast, and Kutluay was putting real work in here, keeping strong guys like Smodiš and Griffith out of rebounding position.

- Manu was a blast. And you can see why Manu’s playing style — ignore the vast difference in talent level for a second — was going to translate better to the NBA than Jarić’s. Jarić was great sucking in the defense and playing kickouts against a collapsing defense, a skill that didn’t match the “staying home” style of defense in the NBA at the time. Manu was a beast getting into the lane. Quick, long, creative, great finishing at the rim.

Attachments

Pingback: Back in Fashion: Milano on the Up and Looking Forward to May

Pingback: BallinEurope, the European Basketball news site » Blog Archive » The Dish: Let’s keep this brief

Pingback: Il Boxscore ideale | Cose di Basket